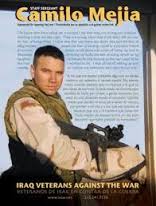

CAMILO MEJIA: CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTOR

Refuge at The Peace Abbey

Mejia surrendered in Massachusetts with the help of the Peace Abbey, an anti-war organization. They helped arrange his transfer back to military custody. Mejia said he was hoping for an honorable discharge as a conscientious objector. (60 Minutes)

Documentary: Interview with Camilo.

http://www.cbsnews.com/news/anti-war-gi-convicted-of-desertion/

Early one afternoon in June 2003, a bushy-haired, 28-year-old sergeant from Miami sat down on the hard floor of a steamy, furniture-less room in Ar Ramadi, one of the most dangerous locations in Iraq’s Sunni Triangle. The space, on the second floor of the city’s government center, had been previously scorched by coalition air raids, but it was quiet that day.

Early one afternoon in June 2003, a bushy-haired, 28-year-old sergeant from Miami sat down on the hard floor of a steamy, furniture-less room in Ar Ramadi, one of the most dangerous locations in Iraq’s Sunni Triangle. The space, on the second floor of the city’s government center, had been previously scorched by coalition air raids, but it was quiet that day.

Sgt. Camilo Mejía checked his M-16. It was ready for action. He also had 210 rounds of ammunition and about six grenades. He adjusted his Kevlar helmet and flak vest, which was draped over his desert uniform, and took a swig from his canteen. The water burned his tongue. Still gripping his rifle, he stretched out his legs and closed his eyes.

Then suddenly he awoke to the sound of three consecutive explosions. About a half-mile away, a crowd of protestors shouted, “No Bush! Yes Saddam!” A fourth blast shook the building and jolted him to his feet. Some Iraqi dissenters were lobbing grenades at the government center. Camilo and his eight-man squad — all members of Charlie Company of the Florida National Guard’s First Battalion, 124th Regiment — rushed up the stairs to the building’s rooftop. An army sniper joined them.

On the ground below the soldiers, outside the entrance, Camilo watched a bomb inside a black bag explode. Several U.S. soldiers scattered.

Soon a boy no older than seventeen emerged from the crowd. Following protocol Camilo trained his M-16 scope on the slender kid with straight black hair and dark skin. Then the boy, who was wearing gray slacks and a long-sleeve shirt, pulled a small black object from his pocket with his right hand. He cocked his arm. A barrage of automatic rifle fire slammed the teenager to the pavement. The grenade exploded harmlessly near his dead body.

Four years later Camilo still agonizes over the moment. “I don’t remember squeezing the trigger,” he says. “But when I took out my magazine, I only had nineteen bullets left, which meant I shot off eleven rounds. Did I hit him with a kill shot? I don’t know because we all shot at him. It’s a tough call, man.”

Four years later Camilo still agonizes over the moment. “I don’t remember squeezing the trigger,” he says. “But when I took out my magazine, I only had nineteen bullets left, which meant I shot off eleven rounds. Did I hit him with a kill shot? I don’t know because we all shot at him. It’s a tough call, man.”

By the time of the young man’s death, Camilo had served eight years in the military, three in the regular army and five in the National Guard. He had fired his M-16 hundreds of times. But the death profoundly affected him. “I didn’t really reflect on it then because I was more concerned with surviving the next mission,” Camilo continues. “But when I came home during leave, and I saw my daughter for the first time since being deployed, I began thinking about what I was doing in Iraq. How could I be a good father if I didn’t stand up for my moral beliefs? Nothing could convince me that there was a reason for being in Iraq.”

Not only did the teenager’s death haunt him, but so did those of the ten Iraqis he and his men shot in the ensuing months. They were all civilians who were caught in crossfire. And then there were their weeping children. “You see these innocent people get killed and you tell yourself it’s justified,” he says. “I just came to the point when I didn’t want to be an instrument of death anymore.”

On March 15, 2004, five months after he went AWOL during a two-week home leave, Camilo became the first soldier to publicly denounce the war. He declared himself a conscientious objector and surrendered to the military. Two months later he was found guilty of desertion and sentenced to one year in the brig. He was busted to private, stripped of all his army benefits, and given a bad conduct discharge, which he is currently appealing.

At first he was a media darling. Journalists from Singapore to Minneapolis to Paris covered his story. Two weeks after he turned himself in, Sixty Minutes aired a Dan Rather interview with the Miamian while he was still in hiding. Peace activist groups such as Amnesty International and Code PINK made him out to be a hero.

Today he has stepped out of the limelight, except for the occasional antiwar rally or television interview. He spends most of his time attending psychology classes at the University of Miami and bonding with his six-year-old daughter. He awaits the publishing of his new book, follows the daily debate in Washington over Iraq policy, and rues the death toll, which has now reached close to 70,000.

Today he has stepped out of the limelight, except for the occasional antiwar rally or television interview. He spends most of his time attending psychology classes at the University of Miami and bonding with his six-year-old daughter. He awaits the publishing of his new book, follows the daily debate in Washington over Iraq policy, and rues the death toll, which has now reached close to 70,000.

But to the soldiers of his brigade and many veterans, he remains controversial. Where some praise him for taking a stand against an unjust war that’s built on deceit, others call him a traitor and coward. “We’re talking about a convicted deserter during time of war,” asserts Tad Warfel, a captain who supervised Mejía in Iraq, and is now a major and assistant operations officer in the Florida army reserve. “Nowhere in history are there any cowards listed as heroes.”

“He’s a momma’s boy,” adds Mike Naugle, a National Guard sergeant who supervised Camilo in Iraq. “No one wants to die, but he took advantage of his unit and abandoned them in the end.”

Camilo Ernesto Mejía was born on August 28, 1975, in Managua, Nicaragua. He was named for Camilo Torres, a Colombian priest who died in combat, and Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the iconoclastic Argentine revolutionary. Four years before the Sandinistas overthrew Nicaragua’s military dictatorship, Camilo’s father, Carlos Mejía Godoy, was a celebrity of the left; his revolutionary songs and radio satire condemning President Anastasio Somoza Debayle’s feared military police captured the zeitgeist of the Nicaraguan people. His music was played throughout Latin America.

But five months after Camilo’s birth, his parents separated. His mother, Costa Rican-born Maritza Castillo, took the youngster and his older brother Carlos to New York, and then to her native country, for two years, before returning to Nicaragua. Back home she began a love affair with Camilo Ortega, one of three brothers leading the Sandinistas. (Daniel Ortega served as president from 1979 to 1989 and recently reassumed the role.)

Camilo Ortega died in battle that same year. “We watched the revolution unfurl,” Castillo recalled during a recent conversation outside a Starbucks in Sunny Isles Beach. Despite her Costa Rican birthright, Castillo is a pure Nicoya, even dropping “que barbaridad” into every other sentence — a common thing among her countrymen. The 52-year-old wears eyeglasses and has brown eyes, dark tan skin, and curly hair down to her chin.

In 1979, following the Sandinista victory, Castillo and her sons moved into a five-bedroom house in a posh Managua neighborhood. The family had a maid and a gardener. Mejía Godoy, who by then had remarried, lived a few blocks away and was a deputy in the Nicaraguan National Assembly. Camilo and his brother soon began attending a school reserved for the children of government officials, including those of Daniel Ortega.

“Since Camilo was a baby he was very sure of himself,” Castillo says affectionately. “When he was about eleven or twelve, Camilo decided he was going to visit his grandfather in Costa Rica without my permission.” He took off alone on a bus, and it wasn’t until he reached the Nicaragua-Costa Rica border that he called his mom. “I ordered him to come home right away, but he wouldn’t listen,” she says. “I had to call the border authorities to send him back to Managua.”

Contacted by telephone in the Nicaraguan capital, Mejía Godoy explains, “We raised [Carlos and Camilo] to be independent. Camilo was very mature for his age. And he always talked about having a career in literature or the arts.”

In 1991, after the fall of the Sandinistas, Castillo and her boys moved again to Costa Rica. Three years later they headed for Miami, where Camilo attended night school at American Senior High in Miami Lakes. Castillo landed a job as a Publix cashier; Camilo worked at a local Burger King, where he swept the parking lot, cleaned bathrooms, and broiled burgers. He had a two-hour break before school, so his days would usually start at 5:30 a.m. and finish at 10:00 p.m.

Camilo didn’t attend prom or graduation. He received his high school diploma in the principal’s office. When he was nineteen years old, the armed forces beckoned him with the promise of financial stability and college tuition. His parents were dead-set against it. “I thought it was a terrible idea,” Mejía Godoy recalls. “I asked him, ‘What are you going to do if you have to go to war?’ But he insisted he needed to do it in order to pay for his school.”

Adds Castillo, “The recruiter filled his head with pajaritos that he would see the world and make a lot of friends.”

Camilo says he joined the army to become independent of his parents. “My father was the official singer for the Sandinista Revolution,” Camilo says. “I guess I wanted to escape it, find my own way, do my own things, and I found the military. I never really thought I would end up in a real war.”

So in 1995 the nineteen-year-old joined the Army and left for Fort Benning, Georgia.

Following basic training, Camilo spent three years of active duty in Fort Hood, Texas. “I was a mechanized infantryman,” Camilo relays. “So I was assigned to a Bradley personnel carrier. My unit used to test all the new weapons systems that the army was buying from government contractors.”

When he wasn’t playing war with the Bradley, Camilo participated in light infantry drills. One of Camilo’s exercises was to help carry and load an M60 machine gun. “The M60 is very heavy,” Camilo says. “It has an extra spare barrel, a mounting system, and you carry a lot of ammo.”

Then a private, Camilo recalls lugging about 100-plus pounds of gear up a hill, then passing through an obstacle course simulating a minefield. Though a three-man team was supposed to carry the M60, he and his partner were required to move it. But he took the tough assignment with humor. “After each exercise we would have this review session where the people involved gave their opinion on what went well and what went bad,” Camilo recalls. “When it was my turn, my reply was, öI don’t know, because there is no team here, I am the team.’ Everyone laughed because I was the lowest-ranking private in the room.”

But his superiors reprimanded him for not being a team player, and ordered push-ups. “I was supposed to suck it up and not be critical,” Camilo says. Yet he did well enough to earn ribbons for army service and national defense, medals for achievement and good conduct, and certificates for good performance and discipline during training exercises before his days at Fort Hood came to an end in late 1998.

Camilo contends he never realized the full implication of his enlistment until he was about to complete three years of active duty. Every recruit who signs a military contract commits to at least eight years. The armed forces give enlistees the option of two to four years of active duty, then the balance in the reserves or National Guard. It’s all laid out in black and white, according to Naugle. That he didn’t realize the commitment “is a crock,” he says. “When I signed my paperwork, it was perfectly clear what my commitment was.”

Camilo claims he was preoccupied with salary and tuition benefits. “I was nineteen years old,” Camilo says. “I was naive. Had I read the contract more carefully, would I have changed my mind? I don’t really know.”

By 1999 Camilo was a weekend warrior in the National Guard, attending community college in Miami. Two years later he transferred to the University of Miami, where he briefly dated the woman who is the mother of his daughter. The relationship ended after two months. In October, weeks after their breakup, Camilo learned his ex-girlfriend, then 33 years old, was pregnant. He’s reticent to talk about the relationship. “There is really not much to say about it,” Camilo says reluctantly. “She was with someone else.”

On June 7, 2000, their daughter was born. A month later Camilo sued his ex-girlfriend in family court to gain shared custody. A year later a DNA test proved Camilo was the father. On March 28, 2002, the former lovers agreed Camilo would pay $1524 in back child support and $316 a month. The woman — whom New Times is not naming — has primary custody, but Camilo is allowed twice weekly visits and some weekends.

In a way, the paternity suit foreshadowed Camilo’s later action. He showed an assertive persona and a penchant for controversy. He became part of his daughter’s life — as he would choose to become part of the protest movement. “I wanted to play a role in my child’s life, so I had to initiate a paternity action,” he says, his only comment on the matter.

In the days leading up to 9/11, Camilo tried to combine being a military man, a college student, and a father. After the invasion of Afghanistan, his mother feared the worst. “I remember back in 2000 Camilo had told me the possibility existed his guard unit could see action in the Middle East,” she says. “The beating of war drums had begun and they didn’t stop.”

But no notice arrived in the mail, and by the upcoming end of 2002 Camilo prepared for the end of his eight-year contract, in May 2003. “I was working as a volunteer crisis counselor for people with AIDS and the homeless,” Camilo recounts. “I was going to apply for the Ph.D. program, and I was looking forward to spending more time with [my daughter].”

On January 14, 2003, during one of his weekend stints in the National Guard, Camilo was cleaning weapons inside the Guard barracks in Miami. “There was a lot of chatter that our battalion was being activated,” Camilo says. Then battalion commander Lt. Col. Hector Mirabile — a career policeman and former comptroller for the Miami Police Department — informed his troops that they had been activated for Operation Iraqi Freedom. Anyone who was serving could be called again until 2031 as a result of a congressional order.

Like it or not, Camilo was going to war.

In late May 2003, Camilo took his squad to Al Asad, an old Iraqi Air Force base that had been obliterated by coalition forces. “Our mission was to help run a prisoner-of-war camp,” Camilo says. “But we weren’t allowed to call it that because we didn’t have the Red Cross or military police there, so it was designated a detainee camp.”

About two dozen prisoners had their heads hooded and their hands tied behind their backs, he claims. CIA interrogators were in abundance. So were former special ops soldiers working as independent contractors.

Among the prisoners were two Iraqi men who had been found holding empty wood crates that allegedly carried explosives, Camilo says. There was also a prisoner who had been caught with a sniper rifle, which he claimed he was using to protect his sheep from thieves. “Later on we learned that most Iraqis own rifles and pistols to defend themselves from rival tribes,” Camilo says. “It took us awhile to stop viewing every Iraqi with a weapon as an armed insurgent.”

Late one night, six months before the Abu Ghraib scandal broke, Camilo alleges he and his squad witnessed and participated in torturing detained Iraqis. “It was not the same type of excessive abuse,” Camilo says. “But that kind of humiliation was taking place from the very beginning.”

Inside a holding cell, two American soldiers deprived four hooded prisoners of sleep for at least two days, he contends. In addition to insulting the detainees with racial epithets (“Get up you goddamned Hajji”) and expletives (“Up, motherfucker, up”), the Americans fooled the Iraqis by letting them sleep for 30 to 45 seconds and then awakening them, Camilo claims. One soldier banged a sledgehammer against the wall. A lieutenant put his pistol to the temple of a prisoner who was sobbing uncontrollably.

For the next six hours Camilo and his men guarded the enemy combatants. “Some of the guys yelled at them to stay awake on my orders,” Camilo says. “They used the sledgehammer, but not the gun.” Camilo contends he was afraid to criticize the treatment. “There were a lot of ways to justify what we were doing, and I used them all,” he concedes.

“Abu Ghraib wasn’t some isolated event involving a few bad apples. High government officials and nameless contractors were calling the shots.”

Sgt. Mike Naugle, Camilo’s superior, says only part of Camilo’s story is true. He denies crimes were committed at Al Asad. “Yes, there was sleep deprivation used,” he says. “I don’t know if you would consider that abuse considering you have terrorist cutting people’s heads off.”

By July 2003 the insurgents had intensified their attacks in ar Ramadi. One day an improvised bomb killed an Iraqi and injured seven others. One American soldier lost his leg and another his eye in the same attack. Soon Charlie Company’s squad leaders received orders to block all of the city’s major intersections during curfew, a mission dubbed “Operation Shutdown.”

Military leaders believed attackers were coming from outside Ar Ramadi, but Camilo insists they were local. “They knew the lay of the land,” he says. “They would escape into people’s homes.”

Operation Shutdown was a disaster from the get-go, Camilo explains. The first mistake, he asserts, was Lt. Col. Hector Mirabile’s order that the platoon squads follow the same procedure for three consecutive nights. “It gave away the element of surprise,” Camilo relays. “He would constantly make us do things that made no sense. There was a lot of resentment against him.” (Mirabile, who is currently a financial analyst in the City of Miami employee relations department, declined repeated requests for comment.)

On the third night of Operation Shutdown an American soldier opened fire with his machine gun on an eighteen-wheeler that failed to stop at a roadblock, killing the civilian driver. No weapons or explosives were found in the truck.

On day four Camilo’s squad walked into a raging gun battle at a roadblock that was being manned by two other squads from Charlie Company. Four soldiers, including a lieutenant, had been seriously injured when their Humvee was hit by either a rocket-propelled grenade or a mine. Shrapnel and bullets tore up one man’s legs and ripped three fingers off another. Two others were cut in the arms and neck.

In response, at another checkpoint, American soldiers with a 50-caliber gun decapitated a man who was driving fast though a checkpoint. Riding in the passenger seat was the man’s child, whom Camilo saw crying next to the corpse.

Then Mirabile ordered yet another night of Operation Shutdown. “It seemed pretty clear that the colonel was using us as bait to instigate a firefight,” Camilo says. “But no one was going to question the chain of command.”

Camilo argues the lieutenant colonel exposed his men to danger unnecessarily. “Mirabile had been in the infantry for twenty years and had no combat experience whatsoever, Camilo says. “That is like being a chef and you never cooked a meal.” Sgt. Mike Naugle also admitted that he had not seen combat in his 24 years until being deployed to Iraq. “The majority of us, between 95 percent to 99 percent I’d say, had never seen action,” Naugle adds.

Private Oliver Perez, who was part of Camilo’s squad, echoed Camilo’s statement. “A lot of the missions put us in harm’s way, almost as if intentionally,” says Perez, who enlisted when he was nineteen years old and left the military in 2006. “It was an unrealistic expectation to have us stay in the same spot, even kind of suicidal.”

A few days after the end of Operation Shutdown, Camilo says he was shown an anonymous letter threatening Mirabile and his family in South Florida if the battalion was not redeployed home. “They were trying to find out who wrote it,” Camilo explains. “I think it had to do with the fact that he wanted to beautify his resume to make it appear that he was hardcore, that he saw combat and that he killed a lot bad guys.”

(Mirabile provided drama for CNN’s Christiane Amanpour, who aired a report five months after Operation Shutdown citing the lieutenant colonel’s 24 years as a Miami cop as his secret weapon in training Ar Ramadi’s then-nascent police force. “Everything is driven by intelligence,” Mirabile commented on camera. On the day of the interview, Mirabile and Amanpour observed a house raid where armed forces turned up a stash of rocket-propelled grenades and a couple of AK-47s. Mirabile informed the camera that the raid nabbed a tribal warlord. “What this reminds me of,” he boasted, “is the old 1978-1986 cocaine cabals we used to have in Miami, where you’d find firepower like this.”)

Tad Warfel, the Pennsylvania-born military man, defends the lieutenant colonel. “Mirabile was a brilliant military strategist,” he affirms. “He never dictated how to carry out the missions. That was the sole discretion of the platoon leaders.” Moreover in fall 2003 Mirabile’s battalion was awarded the Combat Infantry Badge, one of the highest honors given to infantrymen.

The real problem was that Camilo lost the will to fight, Warfel contends. “He was scared. We were in the most dangerous city in Iraq. There were always grumblings about the missions we did.”

Naugle agrees: “Camilo’s casting unfair blame. There was no way to accomplish that mission without closing the streets off.”

During the third week of September 2003, Camilo approached Warfel about ending his military service. He pointed out that he had fulfilled his contract four months earlier, and that his U.S. residency was about to expire. By federal law, he said, he should be discharged.

But Warfel didn’t approve. Instead he accused Camilo of cowardice and allowed him a two-week leave. Before signing the papers, though, Warfel asked Camilo to pledge he would return. “I remember it like it was yesterday,” Warfel says. “He looked me dead in the eyes and promised me he was coming back.”

At the time, National Guard soldiers rarely got leave. “Camilo was bumped to the top of the list because he said he was going to take care of his green card issues,” says a seething Naugle. “To take that slot away from another soldier and abuse it the way he did is unforgivable.”

Camilo jumped on a convoy truck headed for Baghdad International Airport, where he boarded a C-130 transport plane. That was the last time he saw Iraq.

On October 4, 2003, Camilo arrived at Fort Lauderdale International Airport and took a cab to his mother’s apartment in Sunny Isles Beach. “When I opened the door and saw him, I just hugged him for as long as I can remember,” Castillo says. “I was just so happy to see him in one piece.”

The following morning, Camilo saw his daughter for the first time in nine months. “I was scared,” Camilo says. “I had changed. I asked myself how could I be a good father knowing I had abused prisoners and killed innocents.”

During the next few days Camilo couldn’t sleep. There was the Al Asad prison camp, the ambush outside Ar Ramadi, the dead teenager with the grenade, the child standing next to his headless father’s body. He didn’t want to return. “There were so many issues going through my head,” Camilo says. “Even though I had no doubts I was fighting an immoral war, I kept thinking about the guys in my unit. Didn’t I have a duty to lead them?”

More than anything, Camilo was afraid of the consequences if he went AWOL. “I was afraid of going to jail,” he insists. “I was afraid I would never see my daughter again.”

Camilo even feared he would be executed. “I was terrified,” he continues. “I felt it would be the end of my life. And I certainly didn’t want to be known as a coward.”

On October 16, 2003, Camilo was supposed to have been on a plane back to Iraq. Instead he stayed in bed. Within a week, he went underground, traveling to New York City to meet with a soldier’s rights organization called Citizen Soldier, where he began to lay the groundwork for his surrender.

Through Citizen Soldier, Camilo met Louis Font, a Puerto Rican West Point graduate who had openly refused to fight in the Vietnam War. Font faced 25 years in prison, and during his one-year trial, he accused Army generals of war crimes against the Vietnamese population. In the end Font was honorably discharged. Font agreed to represent Camilo in his eventual court martial.

On March 15, 2004, on the first anniversary of the Iraq war, Camilo came out of hiding. The former soldier and about ten family members gathered at Peace Abbey in Sherborn, Massachusetts, outside Boston. The 21-year-old countryside retreat was founded by a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. After a mass, throngs of television and print journalists congregated at the abbey’s entrance for a press conference.

On March 15, 2004, on the first anniversary of the Iraq war, Camilo came out of hiding. The former soldier and about ten family members gathered at Peace Abbey in Sherborn, Massachusetts, outside Boston. The 21-year-old countryside retreat was founded by a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. After a mass, throngs of television and print journalists congregated at the abbey’s entrance for a press conference.

Camilo announced that he would apply for conscientious objector status. “It didn’t seem like it was a big sacrifice anymore,” Camilo says. “There are so many people who are suffering in Iraq; more than 50,000 dead since the invasion. What is one person going to jail if it can make a difference and help end this war? But it took a long time to get that point and say it is not that big a deal if I go to jail.”

His father, Carlos Mejía Godoy, who rarely visits the United States, stood nearby. “What my son did was very special,” he says. “He did not run away. He didn’t disappear. He accepted his fate and took his punishment.”

After the press conference concluded, Camilo and Font drove to Hanscom Air Force Base, twenty minutes away, where the ex-staff sergeant surrendered to two military policemen. He was then transported to the National Guard Armory in North Miami. Two days later, Camilo was in Fort Stewart, Georgia preparing for a court martial.

During the proceedings that followed, the military judge did not allow Camilo’s defense team to call expert witnesses. The defendant was also denied the opportunity to present his allegations of prisoner abuse and other war crimes as the basis for his refusal to rejoin the war.

Private Oliver Perez was one of the two soldiers in Camilo’s unit allowed to testify on his behalf. He told the jury that his sergeant always “led from the front.” “He often questioned the higherups when others wouldn’t say a word,” Perez says today. “Camilo was a great leader and a great soldier. I’d fight alongside him any day.”

Private Phillip Estime told the court that Camilo was like a father figure. “He looked out for us,” the Haitian-American trooper said. “He put us before himself.”

On May 21, 2004, a military tribunal found the sergeant guilty of desertion and sentenced him to a year in prison. “I sit here a free man. I will sit behind bars as a free man,” he told the tribunal. “I followed my conscience and provided leadership.”

Among those who testified against him was Tad Warfel, who told reporters, “It was a great day for the army, a great day for the Florida National Guard, and a great day for soldiers.”

Ten days after his sentencing, the 126 men from Charlie Company came home. Unlike Camilo, they served thirteen long dangerous months in Ar Ramadi, conducting perilous missions, sometimes with less ammunition and fewer supplies than regular troops. Battalion members earned 24 Purple Hearts. Warfel was among the wounded. He had taken shrapnel in his left forearm.

Soon Camilo was moved to a military prison in Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where the great Indian warrior Geronimo had died in captivity. He stayed two weeks in an isolation cell. “I was kind of a political celebrity then,” he says. A month later Camilo joined the general population. He and the other prisoners would wake up at 4:30 a.m. They’d clean their barracks, eat breakfast, and report for work. “I washed dishes for maybe four, five months straight,” Camilo says. “Around 5:45 p.m., we would get recreation time. We could work out at the gym, play billiards or ping-pong in the game room, or go to the library.” Among the books he read: the Bible, The DaVinci Code and Vaclav Havel’s Disturbing the Peace.

On June 14, 2004, Amnesty International Secretary General Irene Khan sent President George W. Bush a letter requesting the commander in chief release Camilo. Earlier that week, the human rights organization had declared him a prisoner of conscience. The letter cited Camilo’s accounts of prisoner abuse and killing civilians as reasons to free this son of Nicaraguan revolutionaries. “While recognizing that Camilo went [AWOL],” Khan wrote, “Amnesty International considers that he did take reasonable steps to secure his discharge legally that Camilo has genuinely conscientious grounds for his objections to the war.”

Camilo’s time in jail was not altogether bad. “I would get tons of mail,” he says. “Most of the people in military prison are not afraid of speaking out, so being a deserter earned me a lot of respect.”

Maritza Castillo traveled from Miami to the small Oklahoma town at least four times. She was amazed at the support shown to her son. “It was very inspirational,” she notes. “They had set up vigils outside the prison with banners in favor of Camilo, and candles at the entrance.”

The hardest moment during Camilo’s incarceration was the time his then-three-year-old daughter came to visit him during the sixth month of his lockup. That day she was wearing a light color summer dress and sandals. Her shoulder length brown hair was pulled back in a ponytail. They spent about two hours together. When it was time to leave, she didn’t want to go. “Daddy, can’t I sleep here on the sofa?” she asked. “Can’t I stay so we can play again tomorrow?”

When she left, Camilo says, it was “like she belonged to a different world, a place I could not enter. That was the first time I truly felt like a prisoner.”

On February 15, 2005, Camilo was freed three months early for good behavior. His mother, his aunt, his stepdad, and his daughter joined local activists in meeting him when he walked out of the prison gates. They all — about a dozen people — drove to a church in Oklahoma City, where Camilo lunched on pasta and drank a glass of red wine.

Camilo was the first soldier to go AWOL and publicly protest the war, but many others followed him. There were 2450 deserters in 2004, according to army statistics released in early April. The number rose to approximately 2700 in 2005 and 3300 last year. Since the fiscal year began this past October 1, 871 soldiers have deserted. The military has also amped up its prosecution of deserters. From 2002 to 2006, prosecutions have more than doubled to an average of 390 per year.

On July 28, 2005, Camilo returned to Fort Stewart, the site of his court martial, to support Sgt. Kevin Benderman, who also was convicted of deserting the war. Since last year Camilo has also sat on the board of directors for Iraq Veterans Against the War. He has crisscrossed the country sharing his story at rallies and vigils, including one this past March 24 at FIU’s north campus commemorating the Iraq occupation’s fourth anniversary.

He’s also appealing his conviction on grounds that he is a conscientious objector. The military defines the term as someone whose beliefs don’t allow him or her to kill other human beings. “I definitely question his timing on becoming a conscientious objector,” opines Naugle. “If he was really antiwar, then why didn’t he declare himself before we deployed?”

Jason Thomas, another Charlie Company soldier adds, “Every soldier fighting the current war willingly signed himself over to the U.S. military. As vehement as an anti-war activist as he is, Camilo did the same thing. So it irks me that some people treat him and others like him as martyrs.”

Even soldiers who supported him acknowledge they resented Camilo for not coming back. “There were a lot of us who didn’t agree with the way he handled things,” Oliver Perez offers. “But I wouldn’t call him a coward.”

Camilo admits the hardest part of his decision to desert the war was leaving his fellow soldiers behind. “These people are my brothers regardless if I didn’t agree with what we were doing,” he says. “The type of bond that we formed in that type of environment is just so strong. So when you develop that bond and then the other person doesn’t want anything to do with you, it’s painful. It is like your brother telling you, ‘I don’t ever want to talk to you again.'”

Yes, he has been labeled a coward and a hero, Camilo continues. “But really I’m neither,” he says. “Refusing and resisting this war was my moral duty. Instead I chose to fulfill my duty as a soldier because I was petrified of the consequences. Coming home back in October 2003 gave me the clarity to see the line between military duty and moral obligation.